Let’s start with the basics. What are power dynamics?

Power dynamics are ways in which power – the ability to influence or control others, resources, decisions, or outcomes – is distributed and exercised. They can exist in a variety of settings, including families, social groups, project teams, departments, organizations, institutions, and even broader societal structures.

And they can take different forms and operate at different levels. For example, at the broad societal level, structural power dynamics, such as gender or racial inequalities, may be embedded within social systems. These power dynamics can shape how individuals and groups are positioned and treated within society. For example, historical legacies, institutional biases, and social stereotypes have all influenced power imbalances and shapes social and economic opportunities for different social groups.

Power dynamics can also show up in interpersonal relationships, sometimes rooted in formal positions of authority, such as a manager-subordinate relationship in the workplace. Such formal typically include hierarchical structures that dictate decision-making authority, control over resources, and the enforcement of rules or policies.

Informal power dynamics, on the other hand, are not based on formal positions but rather on personal attributes, perceived expertise, social networks, or persuasive abilities. These dynamics can emerge within groups or social settings where individuals with such characteristics hold more influence or social capital. Those with more power often have a greater ability to assert their views, shape the agenda, and influence outcomes, while those with less power may struggle to have their voices heard or to exert influence over decisions.

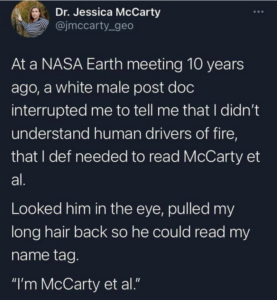

Power dynamics can show up in myriad ways in both virtual and in-person settings. They can manifest verbally, with some individuals interrupting or speaking way more often than others – or simply speaking more loudly to literally drown out other voices. Those with more power might also take up more physical space or be more physically active through facial expressions or gesticulations. And lastly, when someone in a position of power – either formal or informal – comments on or explains something to people from non-dominant groups in a condescending, overconfident, and oversimplified way (when done by a male, sometimes referred to as “mansplaining”).

Some examples that I’ve had the misfortune to witness in groups of which I’ve been a part or facilitates:

Some examples that I’ve had the misfortune to witness in groups of which I’ve been a part or facilitates:

- Woman confidently offers her perspective. Woman listens to two men with more advanced degrees (not relevant to the question at hand) put forth a different opinion. Woman announces she has changed her mind because “they know better than me.”

- In a virtual meeting, woman of color offers opinion that organization should provide financial compensation to members of its community advisory group, to make participation on the board more accessible to individuals with fewer resources. Two white members of the group with more advanced degrees immediately voice their protest. No one else in the group speaks. Woman goes off camera. Doesn’t speak again in the meeting. Eventually resigns from the group.

In each of these cases, the opinions and preferences of those from traditionally dominant groups used their positions, sociodemographics, and literal voices to push through their opinions and preferences. While I’ve offered just a few examples here, I’ve witnessed scenarios like this in spades. And I’d guess you have as well, but maybe (even sometimes) didn’t realize it.

What impact do power dynamics have?

At their worst, and unfortunately more often than not, power dynamics can lead to the marginalization, oppression, or exploitation of individuals or groups. When power – either formal or informal – is concentrated in the hands of a few, it can create barriers to equal participation and decision-making. This can limit opportunities for those with less power to influence the outcomes of a discussion, meeting, or project. It can also result in “groupthink,” where people defer to the opinions expressed by those with power and disregard dissenting views. This, in turn, can lead to resentment and dissatisfaction among those they are excluding – typically those without power.

Are power dynamics always bad?

While my reflexive answer is “yes,” there are some potentially positive outcomes of power dynamics. For example, people can leverage their power constructively to facilitate collaboration, achieve goals, distribute expertise, and create positive change. They can also use it provide guidance, inspire others, and drive progress.

For example, a leader with formal power (e.g., the meeting facilitator or chair) can use her authority to lead an agreed-upon decision-making process, enforce deadlines, and ensure accountability. Similarly, a group member with informal power (e.g., someone with an advanced degree or unique skill set) can use his expertise to provide guidance and support to others.

The key is, those with the power must decide to do these things – a choice that may not come naturally.

How can you prevent power dynamics from causing harm?

A complete answer to this question would, no doubt, call for much more space than we have here (stay tuned for more on that). To get started, here are some high-level approaches that you may want to “try on”:

- Pay attention and recognize when power dynamics show up. Listen closely. Observe how often and with what words people from traditionally dominant or other power-based groups are speaking at meetings you attend. Look for the impact that these louder voices have on others in the room and on the outcomes of the meeting. Journal your observations and thoughts so that you can refer to them over time and identify patterns.

- Encourage the establishment of “ground rules.” Whether you are the meeting facilitator or a participant, suggest that the group create a list of meeting norms or rules to which everyone agrees to adhere. These can include guidelines around interruptions, speaking respectfully, and making space for others to share their thoughts.

- Consider motivations. There are many reasons a person could be dominating a conversation or meeting. For example, they may feel strongly about a particular topic, or they may have a personality that tends to dominate social situations. By understanding these factors, it can be easier to address the issue in a productive and respectful way.

If you would like to take a deeper dive into managing power dynamics in your groups or meetings, please

to request our free, new guide entitled, 10 Steps to Managing Power Dynamics in Your Meetings.

Thank you for reading. Reach out to us at stacey@chazinconsulting.com if you would like to talk about how we can work with you to design and facilitate meetings that are inclusive, effective, and minimize the negative impact of power dynamics on your goals. Please also follow us on Facebook or LinkedIn, where we promise not to overwhelm you with meaningless chatter.

0 Comments